100+ Surreal Movies: A List of Trippy Films

Wondering what qualifies a surrealist film? Here are the best and most trippy surrealist films.

Table of Contents

Surrealist Cinema, Defined

What exactly makes something a surreal movie? What are surreal films? What is the defining characteristic of surrealist cinematic history? Here are the main traits of surrealism in movies. Mind-bending, crazy and trippy visuals are surely one component, but let’s go even deeper. Here are four critical elements.

1. Secret glitches in reality and trippy nuances. Surrealist movies often have strange “Easter eggs,” or glitches, in them that are meant to subconsciously put the viewer in a phantasmagorical state where they are questioning what is reality and what is fantasy. For example, in David Robert Mitchell’s It Follows (2014), the movie is intentionally filled with subtle anachronisms and glitches that give you the feeling that something is deeply off with the setting. Similarly, in An Andalusian Dog (1929), the film has no real sense of linear or chronological time but assumes that is normal. This kind of irrationality underpins great surrealist movies.

2. Impressionistic, psychedelic, or bizarre cinematography. While impressionism and surrealism in traditional art history are different movements, they share a common thread because they both distort and play with visual reality in highly subjective ways. What one visually sees in a surrealist film is not so much what is there, but a haze of what can be imagined to be there. Take for instance the way the movie The Tree of Life (2011) blends normal sequences of mundane moments with dreamscapes, with hazy memories, and then with psychedelic imagery from beyond the terrestrial plain. Or the way Suspiria (1977) brings unnatural colors over almost everything, yet it still feels real. Or for the most literal instance, consider Enter The Void (2009), which never has a stable camera; the focus is constantly being lost, and actual visual distortions are rampant throughout the movie.

3. Uncertainty about artistic intent, misunderstanding, and gonzo dynamics. All good movies leave you guessing. But a common trait in surrealist films is to intentionally make the film’s meaning very hard to decipher, to turn the film’s deeper message into an unreadable hieroglyph where the viewer can project whatever meaning they want onto it. The most extreme example of this is Freddy Got Fingered (2001), a movie lacking any semblance of rationality. How did a major distributor and production house green-light and market a so-called comedy film with a title explicitly about child abuse? Why does Freddy’s abuse have almost nothing to do with the plot of the film? A less extreme example is how a movie such as Donnie Darko (2001) American Psycho (2000), or Sorry to Bother You (2018) end on notes that seem to intentionally cast doubt on everything you just watched, making you reconsider what actually just happened.

4. Ripples in the fourth wall and other meta commentary. The third wall is what separates you as viewer of a movie and the plot/characters partaking in it. When the characters in the movie acknowledge your presence as a viewer of media, they are breaking the third wall. Most surrealist masterpieces aren’t so explicit in having the characters talk to the viewers, but they often do emit a certain nuanced awareness that makes clear the division between the movie and real life. A famous example of this is Being John Malkovich (1991), which is about people finding a portal to take over the body of the real-world actor John Malkovich; that is, a movie about a movie star with a totally irrational plot. Alternatively, The Twilight Zone episode “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” (1964) or Vanilla Sky (2001) also use the format to trick the viewer into thinking they are seeing one thing, when they are actually seeing something else.

Is this what you thought of when you thought about cinematic surrealism? It should be because many of these practices, although they evolved along with technological progress in media, are grounded in the works of Salvador Dalí, Leonora Carrington, Max Ernst, and other surrealist painters that distorted visual reality, time, and the relationship between viewer and artist.

That said, there is also a surrealist artistic and political movement, which is what is considered part of official historical Surrealism — with a capital “S” — and was grounded in artistic and intellectual manifestos from the 1920s. Here, our definition of surrealism is not so limited. For this list, any movies that scream with absurdity, redefine the boundaries of reality, or paint the screen with intensely poetic strokes, we consider it surreal cinema.

Now that we have explained the origins of surrealist cinema and defined some borders on what makes a movie surrealist, let’s look at some of the best surreal, mind-bending films out there. Let’s get into the trippy movies.

Old Surreal Movies

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

The grandfather of all cinematic surrealism, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) is a collaboration between surrealist filmmaker Luis Buñuel and surrealist painter Salvador Dali. According to Buñuel, he was sharing a meal with Dali at a restaurant one day when he recounted his dream of a cloud slicing through the moon like a razor slicing through an eyeball. Dali responded that he’d recently dreamed of a hand that was crawling with ants. Upon hearing this, Buñuel said, “There’s the film, let’s go and make it.” Only 21 minutes long, this silent film includes the infamously nauseating opening scene where a straight razor slices open a woman’s eyeball. Buñuel also said that the only rule in making this film was that nothing was to appear rational—instead, it was to emulate the human dream state in its purest form: “In the film the aesthetics of Surrealism are combined to some of Freud’s discoveries.

The film was totally in keeping with the basic principle of the school, which defined Surrealism as ‘Psychic Automatism’, unconscious, capable of returning to the mind its true functions, beyond any form of control by reason, morality or aesthetics.”

Fireworks (1947)

Filmmaker Kenneth Anger is perhaps best known not for his films, but for writing the scabrous tell-all, Hollywood Babylon. But in what is called “the earliest of his works to survive,” Fireworks is startlingly risqué for the late 1940s. The film, which Anger shot over a long weekend in his parents’ Beverly Hills home while they were away, lasts only 13 minutes and appears to take place in a constant dream state. The dreamer (Anger) enters a gay bar that just so happens to be adjacent to his bedroom and finds an extremely muscular shirtless sailor posing for him. But when Anger attempts to touch the sailor, he is beaten. More sailors join in to beat him. Anger says he was inspired to make the film after reading about LA’s “Zoot Suit Riots,” in which gangs of white sailors randomly beat up Mexicans. Due to its explicit gay themes, Fireworks was immediately deemed obscene, a ruling which Anger has successfully fought over the decades.

The Exterminating Angel (1962)

A formal dinner party among the elite at a sprawling mansion turns sour when the attendees suddenly realize they are unable to leave. Over the days they grow hungry and quarrelsome. An older attendee dies, while a young couple commits suicide in a closet. Although director Luis Buñuel made a practice of never explaining what his films were supposed to mean, film critic Roger Ebert apparently felt he’d figured it out: “The dinner guests represent the ruling class in Franco’s Spain. Having set a banquet table for themselves by defeating the workers in the Spanish Civil War, they sit down for a feast, only to find it never ends. They’re trapped in their own bourgeois cul-de-sac.”

Scorpio Rising (1964)

A highly stylized and visually stunning dialogue-free 28-minute film from Kenneth Anger, Scorpio Rising features a soundtrack of 50s-style rock ‘n’ roll to depict Scorpio, a bored gay biker with a fixation for Hitler, James Dean, Marlon Brando, and Roman Catholicism getting ready to go out riding one night, only to meet with death face-to-face. At its premiere, members of the American Nazi Party protested, claiming that the film irreverently depicted the swastika. The theater where it played was also raided by vice cops because there are flashes of genitalia in the movie.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)

Another offering by surrealist master Luis Buñuel, the plot is almost the direct inverse of his 1962 film The Exterminating Angel—whereas the upper-crust celebrants in the previous movie found they were unable to leave a dinner party, this time around, they find they’re unable to get a meal anywhere. The best they can manage is a free drink of water. Murders abound, and dreams and reality intertwine to the point where they are indistinguishable.

What? (1972)

What? by Roman Polanski is an X-rated nudity extravaganza that meanders through meaninglessness so extreme that title itself, What?, is a reference to the film’s absurdity. The movie was supposed to be called Diary of Forbidden Dreams, but after one of the actors watched the film, he said: What? as if to say, what what that? Is that even a movie? What?!!? If any semblance of rationality is to be gathered about this film, you could call it an erotic retelling of Alice in Wonderland, except Wonderland is a villa in Italy filled with rapists, pimps, priests, a nurse that loves Nietzsche, and art collectors.

In many ways, What? is the ultimate precursor of Harmony Korine’s sexualized and nonsensical surrealist movies such as Spring Breakers and The Beach Bum. Just like in Korine’s films, in Polanski’s What?, psychedelic absurdity mingles with bizarre humor that mingles with unapologetically pornographic energy set against smooth cinematography and a beautiful setting. Supposedly Polanski thought this was going to be his best movie, when it fact only did $64 at the box office. One critic on IMDb explains an interesting theory about where Polanski’s head might have been at when he made this film:

I’ve never seen a movie that feels more like an off-his-rocker director who’d recently found fame and riches, likely on a drug binge, using his funding to basically say **** you and splooge all over his entire audience, by making a completely ridiculous, meandering, pointless, and entirely nonsensical “movie,” which of course stars a strikingly gorgeous lead actress who is half-naked the majority of the time.

I am a huge fan of Roman Polanski’s early filmography (60’s-70’s) but I swear he must have been on a drug BINGE when he decided to make this movie. Thriving after the success of Rosemary’s Baby, binging on who knows what, and thinking “I can do whatever I want, so I’m going to do this, LOL”. One of the most careless celluloid jerk-off’s I have ever seen. Is Sydne Rome beautiful? Yes. Is the movie hilarious? Sometimes, but not usually. Does it have a plot? No. Is there any sort of structural progression to it? No. Is it hilarious that he made it? Yes. Will I ever watch it again? Probably not.

The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973)

You might say there are two types of surrealist films. There is pop surrealism and there is surreal surrealism. Pop surrealism employs surrealist aesthetics and moments of absurdity but falls back on traditional narrative structures to give the story a tidy ending or at least a sensical and linear progression; think of Tim Burton films that, however fanciful, still are intelligible to a mainstream audience. Then there is surreal surrealism where everything is so upside down down that any intelligible marker is impossible to find and all norms are suspended — this is surreal surrealism, and The Hourglass Sanatorium from Polish director Wojciech Jerzy Has is about as surreal of movie as they come.

The Hourglass Sanatorium (Polish: Sanatorium pod klepsydrą) is a movie that touches on and shuffles up all concepts of politics, cultural identity, and conventional storytelling. Of all the films on this list, it might be considered the most surreal of the surrealist films; a real trip.

Eraserhead (1977)

For better or worse, surrealist cinematic history is very much defined by filmmaker David Lynch; film critic Pauline Kael famously dubbed Lynch “the first popular Surrealist” — and all of his films, starting with his debut Hollywood release Eraserhead and into his legendary TV show Twin Peaks, are staples of modern surrealism. Lynch’s creations have a trademark eerie set design with deeply memorable and bizarre characters. While on Lynch films are surrealist through and through, Eraserhead started it all and is the foundational work of Lynch’s future career: experimental, darkly humorous, and bursting from the seams.

Due to fundraising difficulties—Lynch actually worked delivering newspapers during much of the filming—Eraserhead took five years to complete. He says the film’s oppressive mood was inspired by living in an oppressive North Philadelphia ghetto: “I saw so many things in Philadelphia I couldn’t believe … I saw a grown woman grab her breasts and speak like a baby, complaining her nipples hurt. This kind of thing will set you back.”

The “plot” of this black-and-white film involves a man with a towering pompadour who fathers a sick, deformed-looking child whose endless wails are headache-inducing. The soundtrack constantly features industrial white noise. As with the best surrealism, the only “logic” here is that of dreams.

Stanley Kubrick (Dr. Strangelove, 2001, A Clockwork Orange) called this his favorite film. Mel Brooks (Blazing Saddles, The Producers) was so impressed that he offered Lynch the opportunity to direct The Elephant Man, which would become Lynch’s second feature film.

Surreal Movies • 1980 – 1999

Pink Floyd – The Wall (1982)

Looking for surreal musicals? For this super-niche type of film, there is only one contender, and that’s Alan Parker’s visual reimagining of Pink Floyd’s 1979 album, The Wall. This movie’s symbolic approach to topics such as fascism, war, drug addiction, and isolation make it a rather universal film that was relevant in the 80s, 90, 2000s, and beyond.

Forbidden Zone (1982)

Forbidden Zone is an absurd, cult classic and while not many mainstream audiences have seen it, they have felt the influence of this musical, as it was deeply influential to Tim Burton. It was directed by Richard Elfman, the older brother of musician Tim Burton, and it was the first cinematic score of Danny Elfman. One critic describes Forbidden Zone as “Looney Tunes as directed by Jean Cocteau” and another reviewer notes paradoxically: “It’s frequently offensive and never clever, but it remains a unique and strangely magical movie.” There is no use in describing the narrative of the movie because it is a surreal journey.

Alice (1988)

In terms of literary surrealism, an important and popular question is often asked: Is Lewis Carroll’s book Alice in Wonderland surrealist? While the book has many surreal elements of melted and distorted reality, the work of Lewis Carroll is not by the definition part of the surrealist artistic and political movement, but from a vantage point of the 2020s, it does make sense — if you’re speaking in broad strokes and in generalities, as we are in this list — to lump anything with mind-bending, out-of-the-box, bizarre visuals and themes as surrealist. There is the surrealist movement grounded in André Breton’s school of Surrealism, and then there are surrealist conceptions of visual aesthetics, which are two different things.

In any case, many creative film people from Walt Disney to Tim Burton have given us surreal visions of Alice and her trippy dream world. Perhaps the most true to surreal aesthetics, though, are in Czech artist Jan Svankmajer’s Alice, an 80s film that brings the bizarre world of Alice to alarmingly disturbing and creepy heights. Svankmajer subverts all sorts of elements and creates an interesting think-space for the nature of the world. The film is made even more surreal by creating a hybrid of live action with stop-motion animation. It is a chaotic and hypnotic film, made even more so for English-speaking viewers because the film is in Czech.

Cabin Boy (1994)

Comedian Chris Elliott (Late Night With David Letterman, Get a Life) operates in the “no jokes, all comedy” format of surrealist TV comic pioneers such as Ernie Kovacs and Andy Kaufman. In this, his film debut as writer and featured actor, he plays Nathaniel, a spoiled-rich “fancy lad” who finds himself on a ship called The Filthy Whore. While out at sea, he sees a ghost as well as a talking, floating, tobacco-spitting cupcake but is rescued by a “shark-man.” He loses his virginity to a woman with blue skin and six arms. David Letterman makes a cameo as the “Old Salt in the Fishing Village,” who tries to entice Nathaniel with the line, “Wanna buy a monkey?”

Dead Man (1995)

Called a “Psychedelic Western” by its director Jim Jarmusch, Dead Man stars Johnny Depp as a man who gets struck with a bullet that is so close to his heart that it can’t be safely removed, effectively making him a “dead man walking.” He befriends a Native American man named Nobody, and they go on a series of misadventures that could only happen in a “Psychedelic Western” film. The ending leaves the viewer confused as to whether it’s real or a dream. Cameo appearances by rocker Iggy Pop and Hollywood legend Robert Mitchum.

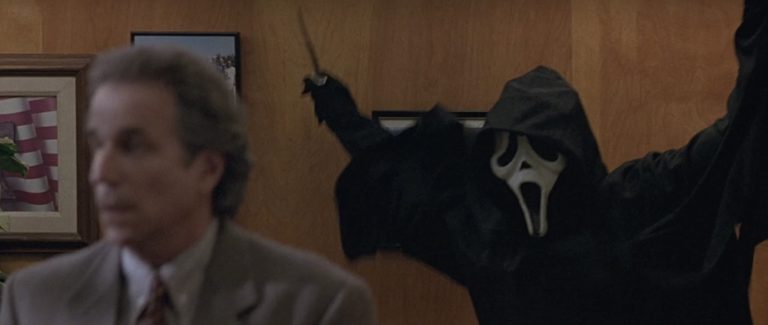

Scream (1996)

We can’t talk about surrealist movies that play with the fourth wall without talking about Wes Craven’s masterpiece, Scream (1996). The film, originally titled Scary Movie, is both a master class in horror-movie tropes and a fun, engaging murder mystery. The characters in Scream exist in the same universe as the viewers; they’ve seen the same horror movies we have, and they are cognizant of “the rules” of horror. Director Craven, who has degrees in psychology and philosophy, often uses horror to examine the nature of reality. For instance: What would a horror movie be like if the characters knew they were inside a horror movie?

The Big Lebowski (1998)

Directed by the Coen brothers, The Big Lebowski is a cult film often associated with stoner culture. Yet what makes this film so funny and so memorable is that you realize once the credits roll that absolutely nothing transpired in the film, except one minor character dies and he dies in a way that has almost no bearing on the movie you just watched for the last two hours. The whole movie, according to Joel Coen, purposely has a “hopelessly complex plot that’s ultimately unimportant,” which creates a truly surreal cinematic experience. Naturally this movie also breaks the fourth wall and has a series of drug-induced psychedelic visuals. One IMDb reviewer writes of The Big Lebowski:

This movie is not funny, it is not memorable, and it is not enjoyable. It’s a story that reads like it was written by some pinhead with ADD who heavily self-medicates with marijuana; a ridiculous amount of random things happened for no damn discernible reason or even a more than tenuous connection between them.

Indeed, indeed, and that is also what makes this movie so good and satisfying, at least to a certain kind of viewer.

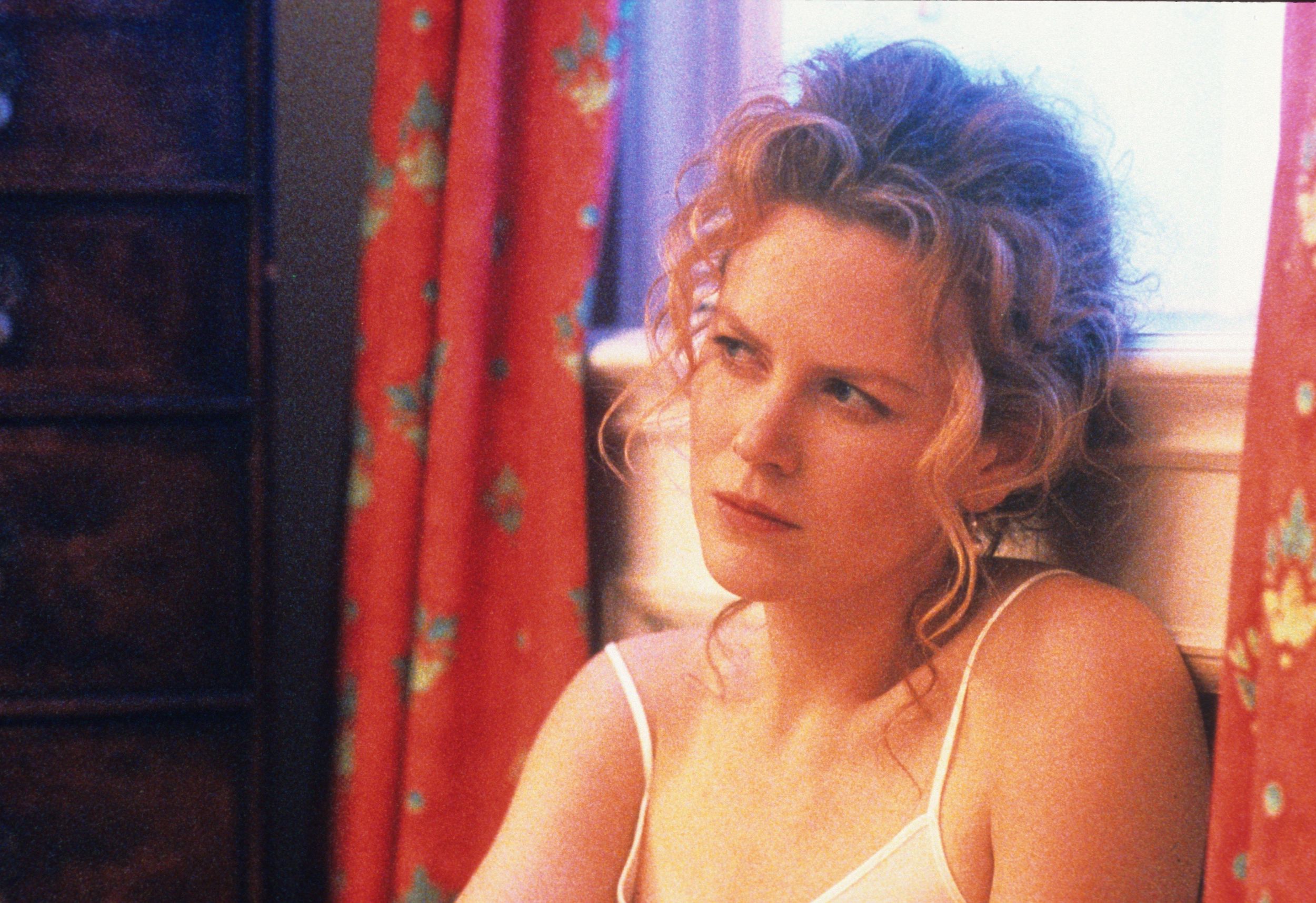

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Like David Lynch, Stanley Kubrick is also one of the great mainstream surrealist filmmakers. Though, the surrealism of Kubrick is often more subtle, more embedded in the atmosphere than directly in your face like it might be in a Lynch film. Kubrick explains his own approach to the surreal as willful embrace of the mysterious: “There’s something in the human personality which resents things that are clear, and conversely, something which is attracted to puzzles, enigmas, and allegories.” Kubrick continues:

I have always enjoyed dealing with a slightly surrealistic situation and presenting it in a realistic manner. I’ve always liked fairy tales and myths, magical stories. I think they are somehow closer to the sense of reality one feels today than the equally stylized “realistic” story in which a great deal of selectivity and omission has to occur in order to preserve its ‘realist’ style.

While so many of Kubrick’s films bend your mind, Kubrick’s last movie before his death, Eyes Wide Shut, is the most directly lavish, poetic, dreamy and controversial of his work. The unsettlingly sexual plot moves in unreal ways but always feels grounded in something commonplace, while the camera has a strange grain, almost like vaseline was on the camera.

Being John Malkovich (1999)

Although the script was explicitly written to star actor John Malkovich, it was repeatedly rejected because even Malkovich said he wasn’t marketable enough—he suggested calling it Being Tom Cruise. But Malkovich eventually signed on to this odd film where Craig Schwartz (John Cusack), a down-and-out New York puppeteer, accidentally finds a portal into John Malkovich’s mind and realizes he can make money selling access to it. Roger Ebert named this the best film of 1999: “Either Being John Malkovich gets nominated for best picture, or the members of the Academy need portals into their brains.”

New/Recent Surreal Movies

Vanilla Sky (2001)

Vanilla Sky is a controversial film. Some critics love it, yet most critics hate it, calling the movie “incoherent jumble” and lambasting the famous director Cameron Crowe for even taking on such a silly project. The Hollywood Reporter says the movie is “as pretentious as it is preposterous,” and the New York Observer cites it as a “good example of what self-destructive cinematic havoc can be wrought by handing over millions of dollars to movie stars to produce their own ego trips.”

So why is this one of the great surrealist masterpieces of the 2000s? The movie uses flashy storylines, dreamy soundscapes, and beautiful cinematography to bury the film’s deeper meaning. On the surface, this is a movie about absurd technological innovation and a cocky narcissist with too much money. Deeper down, it’s an existential fairy tale about the fact that no matter how much technology progresses, no matter how good-looking you are, and no matter how rich, you’ll never be able to overcome death and you will die, and when you die you will be denied the love you spent your whole life seeking. Like all great surrealist masterpieces, Vanilla Sky works like a mirror and doesn’t hit you over the head with a prepackaged moral. What you think about it tells you more about yourself and your values than it does about the film.

Philosophical messaging aside, Vanilla Sky is also a noteworthy surreal film simply for how ambitious the concept is, being a dream within a dream within a dream film. The film’s visuals were inspired by Impressionist painter Claude Monet, particularly his paintings of clouds.

Freddy Got Fingered (2001)

Tom Green’s Freddy Got Fingered was released in the early 2000s and upon release was frequently criticized as one of the worst films ever made. In a now famous review, film critic Roger Ebert refused to even give it one star, saying: “This movie doesn’t scrape the bottom of the barrel. This movie isn’t the bottom of the barrel. This movie isn’t below the bottom of the barrel. This movie doesn’t deserve to be mentioned in the same sentence with barrels.” Yet he also said: “The day may come when Freddy Got Fingered is seen as a milestone of neo-surrealism. The day may never come when it is seen as funny.” Roger Ebert, though, later revised his review saying the film did have some merit he missed.

What is that merit? It’s extremely difficult to tell. It is by no means a good movie, but it is certainly one of the most perplexing, spontaneous, nonsensical, meta-funny, and disturbing films in existence and as such a really good movie. The wormhole of explaining how this paradox can be true, the contradiction of how the world’s most famous film critic, Roger Ebert, flip-flopped on this film, how you can watch the movie and see it as crap or a masterpiece, is exactly why this is one of the best surreal films made on planet Earth.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005)

British author Roald Dahl originally wrote Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as a children’s novel. Like Alice in Wonderland, the book reimagines what reality can be and assigns an absurd degree of power to the human capacity for imagination. The book, like many of Dahl’s books, inspired Mel Stuart’s Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory (1971) and Tim Burton’s 2005 Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. In many ways, all of Tim Burton’s films can be considered surreal, particularly Beetlejuice (1988), Edward Scissorhands (1990), The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), and Big Fish (2003).

Enter the Void (2009)

French director Gaspar Noé provides one of the most literally surreal films on this list with Enter the Void, a movie that both in plot and cinematography mimic a psychedelic trip with all the terror, confusion, and beauty associated with it. Add into that a setting in the neon maze of Tokyo, where the film is set. This movie is a good reference for a film that goes above and beyond to cinematically induce an altered state, and as one critic notes, it brings you to a “surreal extreme.” Whether or not you want to go to that place and whether it’s a good movie are completely different questions.

The Tree of Life (2011)

Terrence Malick is one of America’s most celebrated filmmakers, and The Tree of Life is often considered his best film. The movie’s aesthetics can be described as ethereal, impressionistic, and striking — a surreal combination. Moreover, while The Tree of Life is a family drama, Malick works into the traditional drama an evolutionary origin story and scenes from beyond the world that create an even more airy feel to the movie.

With performances from Brad Pitt, Jessica Chastain, and Sean Penn, The Tree of Life is a stellar adventure visually, philosophically, and just as a piece of entertaining cinema from Hollywood. Likewise, Malick’s film Knight of Cups (2006) dives even more into experimental cinematic states and is an almost dialogue-free surreal — edging on the sublime — movie starring Natalie Portman, Christian Bale, and Cate Blanchett.

Cabin in the Woods (2011)

Cabin in the Woods is the ultimate postmodern horror movie of the 2010s. By that, what is meant is that this movie is comically aware of itself to the point that for a first-time viewer it is incredibly disorienting. The director, Drew Goddard, managed to make this Cabin in the Woods enjoyabl,e though, despite all the surrealist mind-bending going on in the film, which is no small accomplishment.

So what is this movie about? It’s a movie about bureaucrats trapping unsuspecting young people on camera and figuring out creative ways to kill them for human sacrifice so they can appease ancient gods, and if they can’t succeed, then the ancient gods will take over Earth again. Meanwhile the thrust of the plot deals with these young people figuring out that they aren’t in an actual horror movie, but in a weird controlled environment that is deeply akin to a movie set and are continually fighting a series of horror tropes attacking them.

Post Tenebras Lux (2012)

This movie by Mexican filmmaker, Carlos Reygadas, is a visual puzzle about rural life. The movie is bizarre, non-linear, beautiful, violent and allegorical. Like so many surreal films, many viewers and critics alike call it self-indulgent. Though the heap of images in this film carry an undoubtedly lyrical pitch that any fan of surrealist cinema will appreciate. In defending his idiosyncratic non-narrative structure, Reygadas says:

We are used to knowing exactly what’s going on when we are watching something, which is very strange because in life it is precisely the opposite. Most of the time in life we are living through things and don’t know what they mean at the time, except at a very superficial level. It is only later they become important, or take on a particular relevance.

Sometimes surrealism in movies can simply be that they resemble real life, and not the organized structure of the film, which is one of the many joys of watching Post Tenebras Lux.

Coherence (2013)

In what may or may not be a comment on America’s seemingly intractable political divide, eight friends in California get together for a dinner party while a comet is passing overhead. To their dismay, they discover that the comet has created a split reality and that whereas their group carries blue glow sticks to navigate the darkness, all eight of them simultaneously exist in a nearby house where everyone carries red glow sticks. Filmed for only $50,000, Coherence has been praised for the actors’ performances, which may bear an aura of spontaneity because the director gave them no dialogue, only a different outline each day regarding the situations they would be in and how they should react.

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

Beloved director, Wes Anderson, has a trademark whimsy that floats gently and beautifully through all his movies. You could call it weird realism or creative realism. Critic Justin Giglio describes the aesthetics of Wes Anderson movies with poetic precision, Giglio writes: “Everything is simultaneously realist and surrealist [in his movies]. Anderson’s vision offers the viewer the uncanny feeling that although what appears on screen seems to belong in a grounded reality, there are elements of abstraction that couldn’t possibly be real.”

While all of Anderson’s films fit the surrealist bill in way or another, particularly The Royal Tenenbaums (2001), The Life Aquatic With Steve Zissou (2004), and Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009), The Grand Budapest Hotel is perhaps his most ambitious, visually poetic and far-reaching movie hence our selection for the best surrealist film from Anderson. It’s a movie about a book where the author tells the story of a story he once heard from someone telling him a story, and is it a complete dramatic but smooth and safe dream of a film.

The Neon Demon (2016)

Film critic Nigel Andrews of The Financial Times describes this Danish horror film as “controlled delirium moving in on surreal derangement.” This an apt description, and it’s probably one of the better true horror films in the surreal genre, filled with stylish executions and nasty horror moments from cannibalism and plenty of gore. If you watch this one, be prepared for a great deal of surreal (and gruesome) sensationalism.

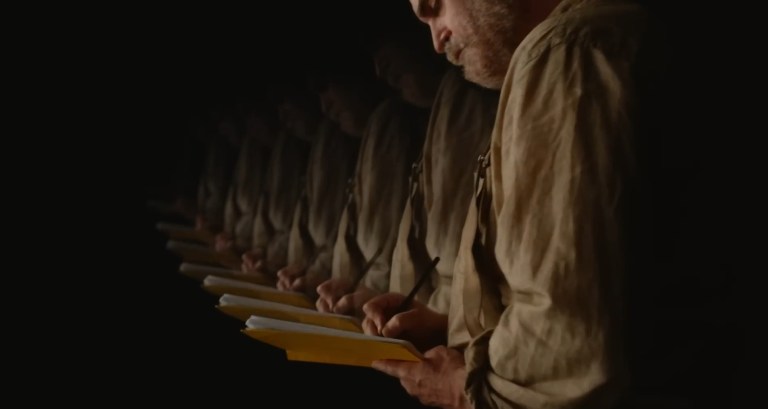

Mother! (2017)

American filmmaker Darren Aronofsky is a master of the surreal genre, particularly with his thriller Pi: Faith in Chaos (1998), a surreal movie about mathematics, religion, and number theory; many also consider Requiem for a Dream (2000) to be a surrealist movie given the dreamscapes and cinematography distortions throughout the movie. Mother!, though is Aronofsky’s most esoteric, symbol-rich, controversial film and perhaps the most surrealist of them all.

Many viewers consider Mother! unwatchable. The sound design is harsh — migraine-inducing, even. The violence excruciating. The storyline on a literal level is absolutely nonsensical. Indeed, the film only works when you watch it not for what is happening on the screen, but as an unfolding metaphor — that what is actually going on in the film is that all the abuse on Jennifer’s Lawrence character symbolizes the abuse that humans do to one another.

Sorry to Bother You (2018)

Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You is a bold addition to afro-surrealism cinema, or the new black Surrealism movement spawned by the work of creators like Ja’Tovia Gary, Jordan Peele and Donald Glover, to name a few. In Sorry to Bother You, the movie begins as a satire rife with meta-commentary and parody, in some ways almost like Office Space (1999), except with black identity in the United States at the forefront. Then the movie explodes in surrealism that is almost unexplainable. As arts journalist, Maya Phillips notes: “It’s a strange time to be black in America—surreal, really. The art tells us no different.” This film perfectly captures that sentiment.

Diamantino (2018)

In some ways this brilliant and colorfully rich film resembles the premise of HBO’s Eastbound and Down. Except in Diamantino, it tells the gonzo tale of a Portuguese soccer star that messes up in the World Cup and then goes on quite the journey. Film critic Glenn Kenny says the movie “feels like an early Adam Sandler comedy remixed by Pier Paolo Pasolini.” Which is to say: Imagine a poetically erotic Adam Sandler movie, eh?

The Beach Bum (2019)

Beach Bum is a Harmony Korine film with incredibly famous faces:

Matthew McConaughey, Isla Fisher, Snoop Dogg, Zac Efron, Jimmy Buffett, and Martin Lawrence. Like The Big Lebowski, this is a vaudevillian film that might be more of a dada film than a surrealist film for the movie’s unapologetically hodgepodge of plot, visuals, and dialogue that add up to nothing but sparkly commentary void of any commonplace realities. Yet the sense of improvisation and subconscious overflowing in this film is intense and deeply surrealist.

Men (2022)

Men is about a woman, Harper (Jessie Buckley), who rents an isolated house in the English countryside to take time to recover from the suicide of her emotionally abusive husband. What feels like a drama and psychological thriller takes a turn for the surreal when viewers begin to realize that most of the men (of all ages) in the viallge are played by the same actor, Rory Kinnear. Seeing the same face on multiple characters is only the beginning of the strangeness though. The finale of Men is a sequence of events that use folk horror and body horror to illustrate a metaphorical meaning that can only be described through uncomfortably surreal imagery.

Beau is Afraid (2023)

After making two hit horror films with Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), filmmaker Ari Aster decided to make an ambitious “nightmare comedy” about a man, Beau, and his relationship with his mother. Viewers follow Beau as his attempts to visit his mother on the anniversary of his father’s death go bizarrely wrong at every single turn. With Beau is Afraid, Ari Aster shows us an entirely subjective point of view that cannot be rationalized into any sort of reality. It’s a movie that tries to make you feel rather than think.

More Surreal Films

The above films were selected based on a certain taste, judgment, and background. We also excluded some movies simply because they have been covered so much on Creepy Catalog. So obviously there are a great deal more surreal movies out there than in the above list. In this section, we’ll catalog those movies for you based as always by chronological order.

- The Seashell And The Clergyman (1928) is an experimental French silent film that depicts a priest who suffers hallucinations as a result of lusting after a man’s wife. It preceded Un Chien Andalou by a year and is considered by many to be the first surrealistic film.

- Last Year at Marienbad (1961) is French-Italian Left Bank movie where time, memory, and space merge in fluid and trippy ways.

- Judex (1963) is a dreamy and odd film with particularly surreal costume design.

- Daisies (1966) Vera Chytilová’s presents a vision of anarchic surrealism and is an important staple of Czechoslovak New Wave movement.

- The Miraculous Virgin (1967) is a mind-bending odyssey through the Slovak art world of the 1960s.

- Birds, Orphans and Fools (1969) an obscure film from Slovak filmmaker Juraj Jakubisko following the tale of three outliers.

- Donkey Skin (1970) is another surrealist musical from France.

- Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) a surrealist dark fantasy movie about a girl with special powers that is part of the Czechoslovak New Wave movement.

- Mysteries of the Organism (1971) comes from Yugoslavia / West Germany by arthouse director Dusan Makavejev and tells the zany story of sexual liberation in the context of communist politics.

- La Belle Captive (1983) is a French avant-garde film where the cinematography is explicitly inspired by surrealist painter René Magritte.

- Dimensions of Dialogue (1983) is a short-but-trippy stop-motion film.

- Getting Any (1995) is a surreal film from Japan in the 1990s and involves a young man’s bizarre journey.

- Dead Head (1986), while technically a four-part mini series on television, we can consider this a movie in form. Watch this one for an interesting British take on a surrealist/noir hybrid.

- The Man Who Wasn’t There (2001) is a mind-bending crime/noir movie from the Coen Brothers.

- American Psycho (2000) is based on the obscene book of the same name by Bret Easton Ellis, and the theatrical version make the plot feel rather suspect and surreal.

- Amelie (2001) is a French film from idiosyncratic director Jean-Pierre Jeunet that bathes itself in magical realism.

- Donnie Darko (2001) is one of the more mysterious and unexplainable sci-fi movies out there, and hence a pretty good artifact of surrealist cinema. For more on this film, read our explainer here.

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004) is a cult classic of surrealist cinema and has such an indie following that it hardly needs any explanation.

- The Taste of Tea (2004) is a Japanese movie that deals with a little girl having to cope with a massive giant duplicate of herself.

- The Science of Sleep (2006) is a trippy and bizarre sci-fi movie.

- Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010) is a Canadian horror flick about escaping a commune.

- Holy Motors (2012) a film about a fluid fever dream taking place in Paris.

- Samsara (2013) is technically a documentary but is something else entirely, a dreamlike reel of beautiful and tragic moments all over the world with an amazing soundtrack.

- Enemy (2013) is a film from A24 and often considered surrealist cinema for the psychological disorientation it brings upon the viewer.

- It Follows (2014) is perhaps the most eerie surreal film on the list from the 2000s.

- Cameraperson (2016) is a movie but it plays like a patchwork poem, fluidly weaving fiction and nonfiction.

- Antiporno (2016) perhaps you can describe this movie simply as a bizarre explosion of colors.

- Get Out (2017) offers a surrealist interpretation of racial tensions with a good dose of traditional horror movie tropes.

- Chained for Life (2019) is a modern indie flick that takes an extreme dive into the world of gonzo surrealism.

- Midsommar (2019) this folk movie leaves you questioning and features a mushroom trip.

- Bliss (2019) belongs, like Enter the Void, in the unwatchable film territory and tells the multi-color and neonized story of a young woman on a deep drug trip that turns her into a vampire. It’s also extremely violent.