The French word noir means “black,” and it was French film critics who first used the term “film noir” around 1946 to describe a budding genre of mostly American films, all of them shot in high-contrast black-and-white, that dealt with crime, despair, femmes fatale, and the ultimately doomed struggle to escape one’s tragic past and future fate.

The hardboiled detective novels of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett served as film noir’s aesthetic backbone, as they featured tough-guy fedora-wearing narrators who find themselves drawn into webs of seduction and deceit by rubbing elbows with manipulative women and sociopathic gangsters.

Although birthed during World War II, film noir didn’t entirely blossom as a genre until that war had ended and Americans were cast into an unprecedented dark haze of apathy and nihilism. More than anything, films noir are evocative of a mood—a very dark mood.

The classic era of film noir is generally accepted to have begun with 1941’s The Maltese Falcon and ended with 1958’s Touch of Evil. Here are some outstanding examples from that genre.

(If you’re looking for neo-noir, which is a different genre inspired by film noir, head here.)

The Best Films Noir

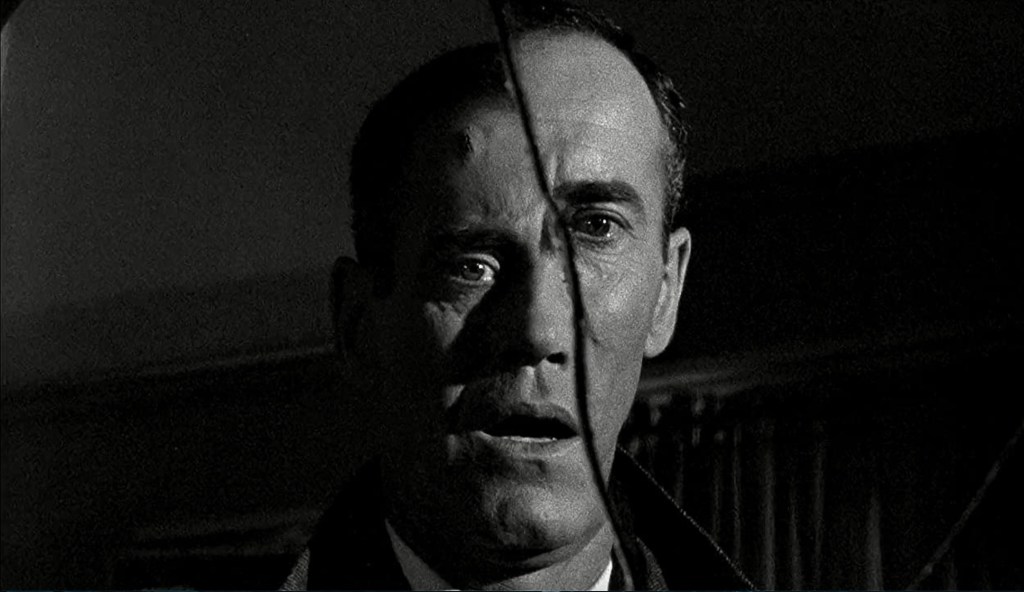

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Based on a Dashiell Hammett novel, The Maltese Falcon allowed Humphrey Bogart to establish himself as the King of Noir with his depiction of Sam Spade, a tough-talking and cynical private eye who becomes entangled with liars of both genders as they all seek to recover the elusive and mysterious falcon statuette. Calling The Maltese Falcon “the granddaddy of noir,” the Independent wrote that “Bogart’s Sam Spade became the model for the cynical yet romantic tough guy antihero that would populate noir for years to come.”

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Dick Powell, normally a lighthearted song-and-dance man from musical comedies, attempts a new persona as Philip Marlowe, the classic detective from Raymond Chandler’s Farewell, My Lovely. The plot involves Marlowe’s attempts to locate an ex-con’s former girlfriend. Four Star Film Fan notes the film’s noirish visuals: “The screen itself is cloaked in shadows, filled with billows of cigarette smoke, and is often superimposed with disorienting images….Aside from Dick Powell’s anchoring performance, Claire Trevor is a tantalizing femme fatale, while Anne Shirley plays the guardian angel rather well.”

Double Indemnity (1944)

Based on the James M. Cain novel, this is director Billy Wilder’s bold foray into the noir genre and is still considered a noir masterpiece. Fred MacMurray, who usually plays a wholesome family man, plays an insurance salesman who is seduced by Barbara Stanwyck into killing her husband. The Independent writes that “MacMurray’s descent into hell as the innovative first-person narrative tells us after the murder, ‘I couldn’t hear my own footsteps. It was the walk of a dead man.’”

The Woman in the Window (1944)

Edward G. Robinson, famous for his depiction of gangsters in 1930s film, plays a straitlaced middle-aged professor who winds up romantically involved with a married woman and murdering her husband. Taste of Cinema writes that “With its emphasis on Freudian psychological explanations for criminal behavior, The Woman in the Window was a ground breaker and certainly is one of the most interesting films from the classic noir period.”

Detour (1945)

A hitchhiking nightclub pianist named Al Roberts (Tom Neal) receives a ride by a driver who then dies on him. He soon assumes ownership of the car as well as the dead driver’s identity, only to be foiled by a licentious femme fatale named Vera (Ann Savage). In the course of sealing Al’s fate, Vera also seals her own.

Scarlet Street (1945)

Venerated German director Fritz Lang had produced movie classics such as M and Metropolis in his homeland before being sent fleeing by the rise of the Nazi regime, sailing to American and embarking on a second career as a noir auteur. Edward G. Robinson plays Chris Cross, a painter who doesn’t correct Kitty March (Joan Bennett) when she incorrectly assumes he’s a famous painter.

The Killers (1946)

In this film adaptation of a 1927 Ernest Hemingway short story, Burt Lancaster—in his first movie—stars as an ex-boxer who is slain by hit men after he “did something wrong once.” The Independent writes, “A smouldering Ava Gardner has a lot to do with Lancaster’s demise, but the film is most famous for its opening 10 minutes as two shadowy figures drive through the New Jersey night, terrorise a diner owner and then blast the acquiescent Lancaster to death, all set to Miklos Rozsa’s doom-laden soundtrack.”

The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946)

Based on a James M. Cain novel, Postman pairs a wayward drifter (John Garfield) with a dissatisfied housewife (Lana Turner) in their plot to murder her husband. Slant magazine writes that “Turner’s character, Cora, is a dark vision of the femme fatale, absolutely empty of any human qualities but raw sexuality, a lust for murder, and a veneer of exaggerated femininity.” The film was remade in 1981 with Jack Nicholson and Jessica Lange in the lead roles.

The Big Sleep (1946)

In perhaps the most famous and revered take on a Raymond Chandler story featuring detective Philip Marlowe, Humphrey Bogart is paired with his wife Lauren Bacall in a tale of lust and intrigue set in Los Angeles. Slant magazine writes, “The Big Sleep is a film that tantalizingly grooves around the edges of things—sex, knowledge, L.A.’s polite society, the very meaning behind the big network of clues and red herrings—and leaves you content to wallow in the murk.”

Odd Man Out (1947)

In an odd change of venue for a noir, Odd Man Out takes us from the shadowy streets of Los Angeles or New York into the war-torn alleys of Belfast, Ireland, where a wounded nationalist leader (James Mason) evades capture after a failed robbery attempt as police are hot on his heels.

Dead Reckoning (1947)

After a soldier inexplicably goes AWOL rather than receive his Medal of Honor, his friend—played by Humphrey Bogart—goes to a small town to investigate and becomes entangled with a femme fatale (his real-life wife, Lauren Bacall) who finally admits to him that she murdered her own husband in self-defense but has been the victim of a blackmail scheme ever since.

Out of the Past (1947)

Sloe-eyed noir icon Robert Mitchum runs away from his past to manage a small-town gas station, only to realize that one can never truly escape their past. He has to return to the big city with all its sleaze, corruption, and deceit. The Independent writes, “Duplicitous dames, hard-boiled dialogue, flashback sequences and world-weary voiceover from the laconic Mitchum all find their apotheosis in a movie that defines film noir.”

Nightmare Alley (1947)

Tyrone Power gives his finest performance as the fairground hustler who works his way into society by means both fair and foul, including murder. But Power’s fall is every bit as precipitous as his rise as he ends up back in the fairground as the carnival geek in this remarkable and disturbing movie. He is entrapped by a woman named Lilith, who secretly records his murder confession and uses it to blackmail him. Sinking in a pool of alcoholism and despair, Stanton ultimately becomes a pathetic geek who bites off chickens’ heads to the delight of carnival-goers.

Sorry, Wrong Number (1948)

Barbara Stanwyck reprises a role made famous by Agnes Moorhead on Broadway as a bedridden woman who overhears a phone conversation that she believes is a murder plot against her. Through a series of flashbacks, she concludes that her husband is setting her up to be killed.

Act of Violence (1949)

This dark and violent offering from director Fred Zinneman stars Robert Ryan as Joe, a bitter POW who seeks vengeance against an American commanding officer named Frank (Van Heflin), who thwarted Joe and his comrades’ attempts to escape a Nazi prison camp. Slant magazine writes, “The men are two sides of the same coin, the fractured identity of the post-war American male: the id, driven by a thirst for justice and revenge, and the superego, willfully repressing the horrific violence of the recent past, trying to blend seamlessly into America’s post-war makeover.”

The Third Man (1949)

Director Carol Reed filmed this story of a pulp novelist named Holly Martins, who travels to postwar Vienna to research the strange death of her lifelong friend Harry Lime (Orson Welles). Critic Matt Noller wrote, “By utilizing the German-inspired visual techniques of wide shots, canted angles, jagged architecture, and expressionistic chiaroscuro lighting, directors like Reed…created an environment of spatial and moral confusion in which their pulpy narratives could take on the ethical weight of a biblical proverb.”

D.O.A. (1949)

Frank Bigelow (Edmond O’Brien) is a man who has been informed he’s been poisoned and only has mere days to live—so he makes it his waning life’s mission to discover who poisoned him and why. Calling it “a philosophically engaging take on venerable film noir themes of isolation, futility and the cruelty of fate,” All Good Movies says that “The basic existential conceit of D.O.A. is not about a man trying to prevent his death; he doesn’t have that power. Rather, it’s all about the desire to know why — why me and why this fate?”

They Live By Night (1949)

Directed by Nicholas Ray (Rebel Without a Cause), They Live By Night stars Farley Granger as an escaped convict who gets injured during a robbery and is nursed back to health by a woman (Cathy O’Donnell) whose kindness causes him to fall in love with her. But despite their newfound love, they find it impossible to maintain their happiness—this is, after all, a film noir.

Gun Crazy (1949)

In a precursor to later films about crazy lovebirds on a crime spree such as Bonnie and Clyde and Natural Born Killers, Gun Crazy stars John Dall as Bart and Peggy Cummins as Annie, two gun-slinging sociopaths who meet at a carnival. Despite falling in love and attempting to straighten out their lives, they find the thrill of the kill too overwhelming to resist.

White Heat (1949)

In his definitive film performance, James Cagney stars as Cody Jarrett, a murderous psychopath with a mother fixation who escapes from prison and leads a heist on a chemical plant. Slant magazine writes that “in the long history of noir’s bleak, unreconciled conclusions, few films attain the sheer nihilistic abandon of White Heat’s finale, with Cagney wreathed by a blazing oil fire as he ecstatically screams ‘Made it, Ma! Top of the world!’ before blowing himself to hell.”

The Asphalt Jungle (1950)

A jewelry heist that was planned as the perfect crime goes horribly awry amid mistrust, double-crossing, and a crack team of police investigators. The Homeless Tribune writes that “The Asphalt Jungle could be understood as a hardening of John Huston’s directorial vision, breaking away from Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon and any greater conquest of cool for pathetic men whose minds have gone rotten from being left on the slab for too long.”

In a Lonely Place (1950)

In what is regarded as Humprey Bogart’s finest performance, he stars as Dix Steele, a troubled screenwriter who is a murder suspect in this noir by Nicholas Ray. He befriends a beautiful woman (Gloria Grahame), who attempts to clear his name of murder until she starts to suspect that he’s guilty. The Independent writes that “Bogart’s volcanic relationship with noir’s greatest good-bad girl Gloria Grahame is the core of a film that contains the genre’s most fatalistic and memorable coda as Bogart reflects, ‘I was born when she kissed me. I died when she left me. I lived a few weeks while she loved me.’”

Night and the City (1950)

Blacklisted by Hollywood during its McCarthyite anti-communist purges, French director Jules Dassin moved to London to film this drama of small-time grifter Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark), whose half-cocked money-making schemes wind up blowing up in his face and alienating him from his business partner (Francis L. Sullivan) and on-again/off-again girlfriend (Gene Tierney).

Ace in the Hole (1951)

Kirk Douglas stars as a down-and-out journalist who used to write for big-city papers but now finds himself stuck out in the vast desert wasteland of Albuquerque, NM. When he attempts to help someone whose story reminds him of his own, he causes chaos and destruction for everyone involved. Slant magazine writes, “In Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas), Ace in the Hole synonymizes interpersonal nastiness with an American’s ultimate right to do whatever the hell he or she wants, because whatever most anyone wants will almost certainly be bad for themselves and everyone else.”

On Dangerous Ground (1952)

In this dark outing by director Nicholas Ray, Robert Ryan stars as Jim Wilson, a tough city cop who is sent upstate to a snowy mountain town to help the sheriff solve a murder case. Critic Fernando Croce writes, “The urban harshness of the city is contrasted with the austere snowy countryside for some of the most disconcertingly moving effects in all film noir.”

Pickup on South Street (1953)

Samuel Fuller was one of the few directors who not only made films noir—he launched the neo-noir genre with his 1963 film Shock Corridor. Richard Widmark stars as a pickpocket who accidentally steals a message that was intended for communist agent, making him the target of a communist spy ring. Taste of Cinema writes, “An unusual story produced at the height of the McCarthy era, Pickup on South Street is a brutal and violent film that barely skirted the production code with its depictions of beatings and life in the mean streets.”

The Hitch-Hiker (1953)

Directed by famed actress Ida Lupino, The Hitch-Hiker tells the tale of two fishermen (Edmond O’Brien and Frank Lovejoy) who pick up a deranged escaped convict (William Talman), who informs them to their horror that he will kill them when their ride is over. They wind up in a Mexican border town relatively unscathed as their would-be killer attempts to take a ferry out of the country.

Angel Face (1953)

Director Otto Preminger filmed this tale of an ambulance driver named Frank Jessup (Robert Mitchum), who falls into the web of a classic femme fatale (Jean Simmons), a spoiled and entitled rich girl who will stop at nothing—even murder—to get what she wants. Noir of the Week writes, “Preminger’s 1952 film is finally a much darker work than earlier 40s noirs, however, as Simmons turns out to be a complete psychopath, an ‘angel of death.’”

The Big Heat (1953)

Glenn Ford stars as a tough cop who seeks vengeance on behalf of a femme fatale (Gloria Grahame), who was disfigured by a deranged thug (Lee Marvin) after he threw boiling coffee on her face. In the process, he realizes that he must now fight an entire crime syndicate. Slant magazine writes, “The Big Heat is truly a hard-boiled film, and its nastiness cleanses the noir of the masculine self-pity that often lards the genre. These men aren’t victims or patsies, particularly of women, who are endlessly destroyed in this film; they’re vicious movers and shakers who go to war purposefully, for their own reasons.”

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Director Robert Aldrich turned this Mickey Spillane “Mike Hammer” novel into a relentlessly dark saga of a female hitchhiker who pulls the storied detective into a disastrous downward spiral over a “great whatsit” that may actually be a nuclear bomb in a suitcase. Slant magazine writes, “Aldrich’s high-contrast, super-dark images and crazy Dutch angles push noir conventions to cartoon extremes; in earlier noirs, these visual affectations implied moral instability, but here their exaggeration signifies a moral vacuum bereft of ethical and spiritual moorings.”

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

Robert Mitchum shines as a sociopathic evangelist with LOVE and HATE tattooed across the knuckles of his hands who marries a widow in a quest to divest her of the money her dead husband had hidden after a robbery. Slant magazine writes, “The film is a nightmare coming-of-age story that concerns a child who learns that adults (and, by extension, their rules) aren’t only fallible, but given to pronounced malevolence.”

The Killing (1956)

In a story that was ultimately lifted by Quentin Tarantino as the plot for Reservoir Dogs, Stanley Kubrick directs the tale of Johnny Clay, a small-time crook who gathers together a five-man team to plot and carry out the robbery of a race track that, naturally, goes horribly wrong. A reviewer for Rotten Tomatoes calls The Killing “a classical noir about a carefully threaded heist unraveled by the scheming of a fiendish femme.”

The Wrong Man (1956)

In this classic noir by Alfred Hitchcock, an innocent man (Henry Fonda) is arrested for armed robbery in a case of mistaken identity. His wife (Vera Miles) takes his side until her own conscience for her past crimes catches up with her. Film critic Eric Henderson calls it “a woefully underrated and truly harrowing study of the psychological cost of misguided suspicion and mistaken identity.”

While the City Sleeps (1956)

In this late-career outing by famed German director Fritz Lang, the city is New York, and someone known as “the Lipstick Killer” has been killing beautiful women throughout the Big Apple. As the story gains publicity, the new owner of a media company offers a job to whomever can crack the case. The Homeless Tribune says, “Alongside Ace in the Hole and Sweet Smell of Success, While the City Sleeps is the most cynical and piercing of noirs to place journalism in its crosshairs.”

Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Screen heartthrobs Burt Lancaster and Tony Curtis star respectively as a shady Broadway columnist and a shifty press agent. Lancaster makes it his life’s mission to persuade Curtis to force his sister to break up with a jazz musician. English film critic Graeme Ross writes, “There are no gangsters, no guns, no one is killed, but Sweet Smell of Success is the blackest of noirs.”

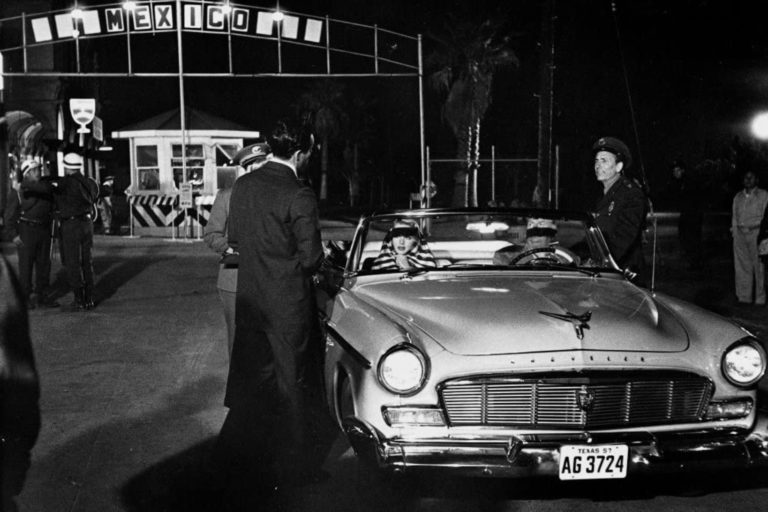

Touch of Evil (1958)

In what is considered both Orson Welles’s last great film and the last film of the entire film noir era, Welles plays a good cop gone bad in a Mexican border town who “never framed anybody—unless they were guilty.” Touch of Evil is perhaps best known for its opening shot, an uninterrupted three-minute tracking scene that ends up with a car explosion at the Mexican border crossing.

Other Films Noir

- I Wake Up Screaming (1941) stars pinup queen Betty Grable as a woman who comes home to find her sister dead and a famous New York sports promoter standing next to her body.

- Ossessione (1942) represent Italian director Luchino Visconti’s purposeful hybrid of noir and neorealism. It is also the first film based on the novel The Postman Always Rings Twice.

- Journey Into Fear (1943) is possibly the first noir film to involve Nazis in the plot. An American agent in Turkey seeks to evade Nazi agents and escape home.

- Laura (1944) starred Gene Tierney in the title role of a woman who got murdered. But we don’t see her for the first two-thirds of the film; it was a case of mistaken identity and Laura is alive and well.

- Mildred Pierce (1945) won the Academy Award for Best Picture and stars Joan Crawford as a woman leading a double life.

- Notorious (1946) is an espionage noir that contains one of the most tense and memorable finales Alfred Hitchcock ever directed.

- Gilda (1946) made Rita Hayworth into a superstar. Hayworth plays the classic noir role of the femme fatale who manipulates two men against one another.

- The Lady From Shanghai (1947) is one of several Orson Welles films noir before his 1948 masterpiece Touch of Evil. It stars Rita Hayworth and contains the classic line “Everybody is somebody’s fool.”

- Dark Passage (1947) was the third of four films starring legendary romantic Hollywood couple Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. Bogart stars as an escaped prisoner who gets plastic surgery to hide his identity. The audience doesn’t see his face for the first hour of the movie.

- The Naked City (1948) is a detective noir about a pair of investigators, one a veteran and one a novice, looking into the murder of an ex-model in New York City.

- Key Largo (1948) was the last of the four films from the 1940s teaming “Bogey and Bacall.” Bogart stars as a combat vet who finds himself at a hotel with escaped Cuban gangsters.

- The Reckless Moment (1949) stars Joan Bennett as a mother who, to protect her family, dumps off the corpse of her daughter’s teenage boyfriend.

- Criss Cross (1949) stars Hollywood hunk as an honest guy who is drawn into a web of seduction and deceit by his ex-wife Yvonne De Carlo.

- Sunset Boulevard (1950) stars Gloria Swanson as a demented and aging ex-Hollywood film star who draws a young screenwriter (William Holden) into her sick fantasy world. Directed by Billy Wilder.

- Strangers on a Train (1951), directed by Alfred Hitchcock, follows two men who meet on a train. One is a man who wants out of his marriage, and the other is a man who hates his father. It is then suggested that they take care of each other’s problem by exchanging murders.

- Jennifer (1953) stars Ida Lupino as a down-on-her-luck woman who takes a job as a caretaker of a recently abandoned mansion where a woman was murdered. Deep shadowing throughout the film induces an impending sense of doom.

- The Big Combo (1955) stars Cornel Wilde as a cop whose attempts to take down a gang boss get complicated when he finds himself sexually attracted to the gangster’s mistress.