Stanley Kubrick Movies: Cinema’s Ultimate Perfectionist

“For the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation.” —Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick (1928-1999) is widely regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers in cinematic history. Nearly all of his films are adaptations of literary works and are notable not only for their realism and striking cinematography, but for their shocking subject matter and innovative use of classical music.

The single element that causes Kubrick’s films to be considered masterpieces was his obsessive drive to supervise all aspects of filmmaking—from conception to completion, he demanded absolute control over every last aspect of his films. From background historical research to ensure an authentic look for each film, to supervising and endlessly rewriting scripts, to forcing actors to retake scenes dozens of times, to choosing the type of cloth the actors’ wardrobes were made of, to the experimental lenses and camera techniques he used, Kubrick was such a demanding perfectionist that he often alienated his actors and crew members.

As an example of his tireless quest for perfection, in arranging the bodies for slaughtered Roman slaves in Spartacus, each cadaver was assigned a number and instructions for its placement.

Kubrick was a tireless editor, claiming at one point that the editing process was what distinguished filmmaking from all other art forms. He notoriously would edit and re-edit films right up to their release date. His final edit of his final film, 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut, was submitted to the studio only six days before his death.

Kubrick insisted on such complete control over his films that he was known to order all unused footage, as well as all costumes, props, and notes, be burned so that no one could ever alter his movies once they were completed.

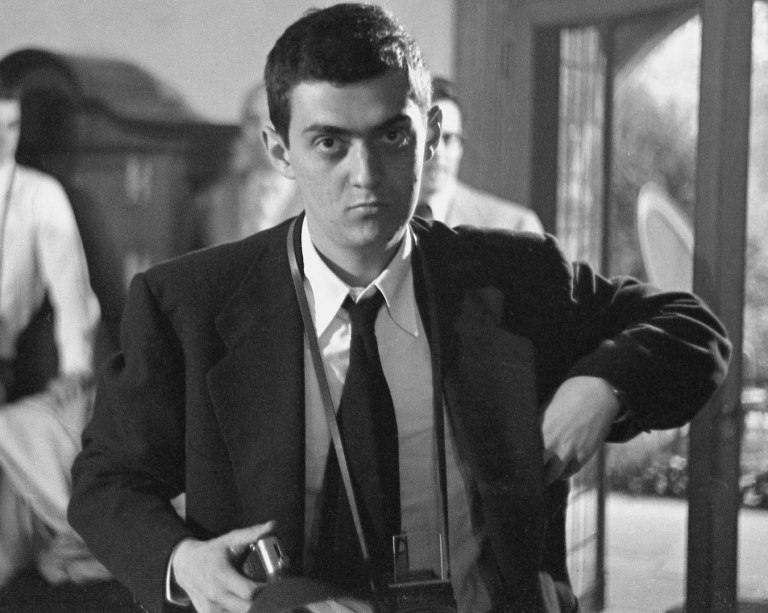

Born in the Bronx and starting out his professional career as a photographer for Look magazine, Kubrick used his tremendous admiration for Orson Welles, another cinematic perfectionist, to transition from still photography into directing motion pictures. From 1951-1953, he made three short films:

- Day of the Fight (1951) is a 16-minute black-and-white documentary about a middleweight boxer named Walter Cartier, tracing a day in Cartier’s life and culminating with him winning a fight with middleweight Bobby James.

- Flying Padre (1951) is a nine-minute black-and-white documentary about a Catholic priest in New Mexico whose parish is so large, he uses a Piper Cub airplane to travel from one remote pocket of believers to another.

- The Seafarers (1953) is Kubrick’s first color film and was made with the approval of the Seafarers International Union. One sequence, which uses a long dolly shot to provide an overview of the seafarers, would become a trademark device in Kubrick’s later features.

Despite his massive fame and unparalleled legacy, Kubrick only made 13 feature films during his lifetime. Here is a guide to his cinematic canon in chronological order.

Stanley Kubrick Movies

Fear and Desire (1953)

Kubrick’s feature-film debut was a 62-minute black-and-white anti-war film that takes place between two unidentified countries. Four soldiers crash across enemy lines and desperately seek a quick way to return to their side of the conflict. They are approached by a pretty young peasant girl (Virginia Leith), whom they tie to a tree with belts. Amid plot twists and turns, they eventually kill the enemy’s general and then return to their home base, where they offer extended soliloquys about the nature of war and how men are not suited for it. In one scene, to create the illusion of fog, Kubrick used a crop sprayer, unaware that it was still filled with insecticide, which nearly killed his crew. Kubrick was reportedly displeased with Fear and Desire and destroyed the film’s original negative.

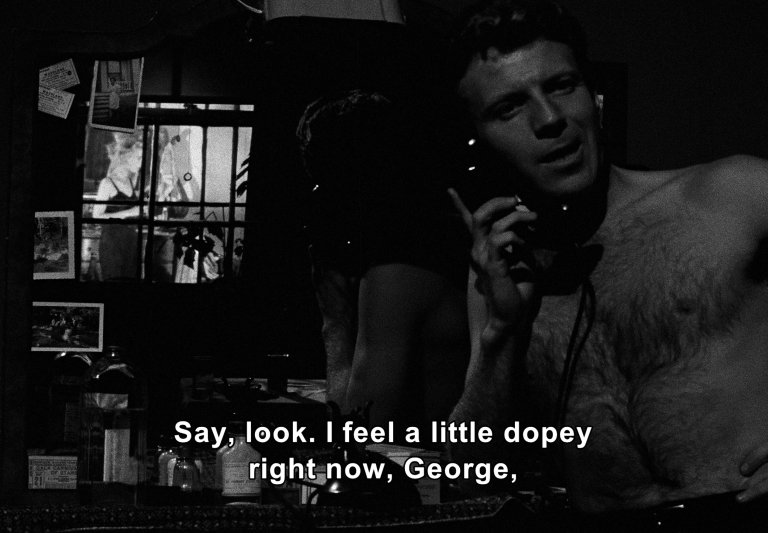

Killer’s Kiss (1955)

A lifelong boxing fan, Kubrick picked up where Night of the Fight had started to direct this 67-minute crime film noir about a down-and-out boxer named Davey Gordon (Jamie Smith) who becomes romantically attached to a woman named Gloria Price (Irene Kane), who makes a living as a “taxi dancer,” which is a woman who is paid to dance with men at dancehalls. Gloria is being abused by her employer Vincent (Frank Silvera), and Davey seeks to rescue her from his violent clutches.

Martin Scorsese would later cite Killer’s Kiss as a major inspiration for his boxing epic Raging Bull (1980). Variety magazine criticized the script of Killer’s Kiss but noted “Kubrick’s talents” and praised his cinematography: “Kubrick’s low-key lensing occasionally catches the flavor of the seamy side of Gotham life. His scenes of tawdry Broadway, gloomy tenements and grotesque brick-and-stone structures that make up Manhattan‘s downtown eastside loft district help offset the script’s deficiencies.”

The Killing (1956)

Another crime film noir, The Killing was based on a novel called Clean Break by Lionel White. Kubrick collaborated on the screenplay with hardboiled novelist Jim Thompson for this story about a ragtag group of lowlifes who conspire to rob a race track in the midst of a horse race by shooting the lead horse and then robbing the money-counting room in the midst of the chaos. The film stars Sterling Hayden, Marie Windsor, Vince Edwards, and Elisha Cook, Jr. Roger Ebert referred to The Killing as Kubrick’s first “mature” film.

Paths of Glory (1957)

The first of two collaborations with already established superstar actor Kirk Douglas, Paths of Glory is based on a novel of the same name by Humphrey Cobb. It is set during the endless brutality of World War I and is based on a real-life story in which four French soldiers were court-martialed and put to death for refusing to engage in a suicidal attack on the enemy. Kirk Douglas stars as Colonel Dax, who went to trial to unsuccessfully defend his underlings against charges of cowardice. Although some criticized the fact that the “French” soldiers spoke with unmistakably American accents and used American slang, the film was a financial success and established Kubrick as a directorial force to be reckoned with.

Spartacus (1960)

Based on the 1951 novel of the same name by Howard Fast and aided with a screenplay by blacklisted Hollywood writer Dalton Trumbo, Spartacus stars Kirk Douglas in the title role as the leader of a slave revolt against the Roman Empire. The film won four Academy Awards and was the highest-grossing film of 1960. Variety wrote, “Spartacus appears to have what it takes to satisfy the multitudes … Kubrick has out-DeMilled the old master in spectacle, without ever permitting the story or the people who are at the core of the drama to become lost in the shuffle. He demonstrates here a technical talent and comprehension of human values.”

Lolita (1962)

This film, based on the 1955 Vladimir Nabokov novel of the same name, marked Kubrick’s first foray into controversy. James Mason stars as Humbert Humbert, a middle-aged man who develops a sexual fixation on Lolita (Sue Lyon), an adolescent but underaged girl. The studio demanded that Kubrick remove the more overt sexual references from Nabokov’s novel, causing Kubrick to later bemoan that if given the chance to go back in time, he never would have filmed Lolita. It would also mark the last time that Kubrick took orders from Hollywood studios, as he soon left his home country of the United States and moved to England, where he filmed his subsequent masterpieces free from censorship but with Hollywood’s full financial backing.

Harrison’s Reports wrote, “You don’t have to be an emulating, prissyish uncle from Dubuque to say that the film leaves you with a feeling that is repulsively disgusting in much of its telling,” adding that “even if the exhibitor makes a dollar on the booking, he may feel a sense of shame as he plods his weary way down to the bank.”

Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Filmed at the height of the Cold War between the United States and Russia, when fear of an apocalyptic global nuclear holocaust was at an all-time high, Kubrick made this dark comedy based on the 1958 thriller novel Red Alert. But rather than aping the seriousness of the novel, Kubrick, after reading extensively about the arms race, decided to make what many consider to be one of the finest comedies ever made.

Peter Sellers shines in three different roles as Merkin Muffley (the US president), Lionel Mandrake (a British soldier trapped at an Arizona military base where a deranged American Colonel sets off World War II by directing his planes to bomb Russia, and the titular Doctor Strangelove, a wheelchair-bound former Nazi scientist.

The Guardian wrote, “”There had been nothing in comedy like Dr Strangelove ever before. All the gods before whom the America of the stolid, paranoid 50s had genuflected—the Bomb, the Pentagon, the National Security State, the President himself, Texan masculinity and the alleged Commie menace of water-fluoridation—went into the wood-chipper and never got the same respect ever again.”

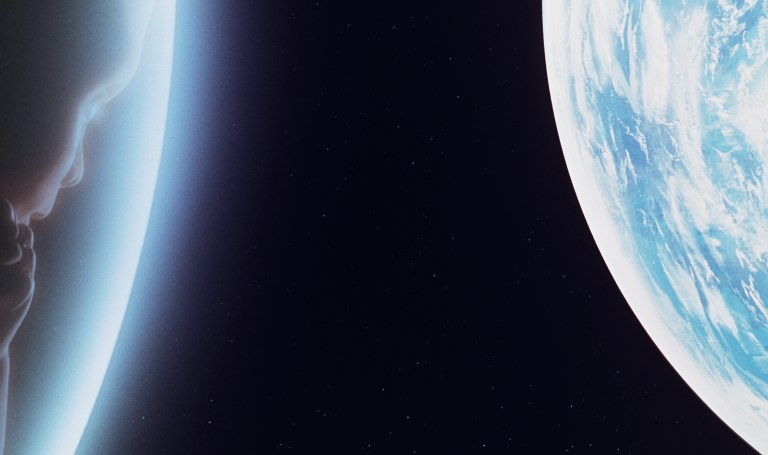

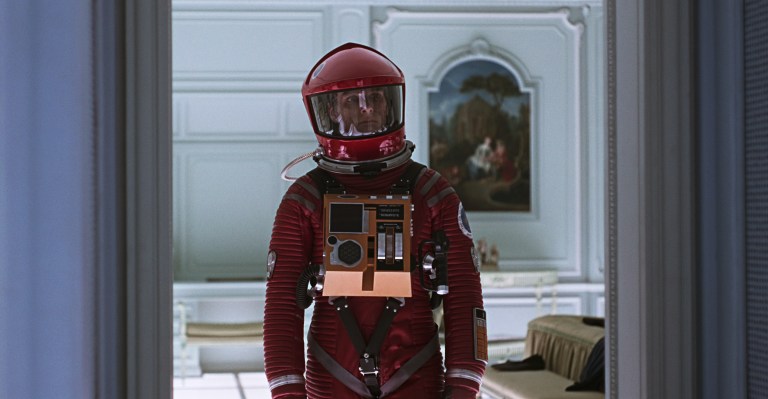

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

In what many people regard as Kubrick’s ultimate achievement and possibly the greatest film ever made, Kubrick cowrote the screenplay with noted science-fiction author Arthur C. Clarke about the intersection of space travel and the process of evolution that took mankind from apes, to mankind, and then onto a spiritual realm far beyond anything humans had ever conceived.

Using very little dialogue, the main part of the film involves a space voyage to Jupiter that is hijacked when HAL, the AI-driven computer that manages the trip, suddenly turns on some of the astronauts and starts killing them.

In an interview Kubrick said, “On the deepest psychological level, the film’s plot symbolized the search for God, and finally postulates what is little less than a scientific definition of God. The film revolves around this metaphysical conception, and the realistic hardware and the documentary feelings about everything were necessary in order to undermine your built-in resistance to the poetical concept.”

Before settling on 2001, alternate working titles included How the Solar System Was Won, Journey Beyond the Stars, Universe, Tunnel to the Stars, and Planetfall.

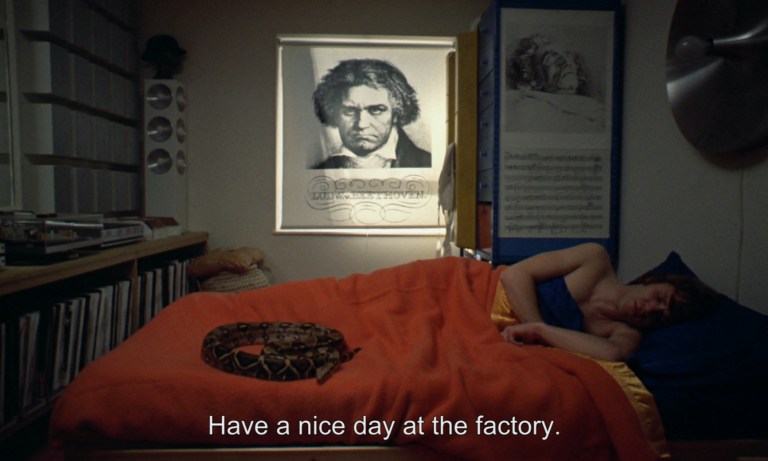

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

In what is possibly Kubrick’s most controversial film—so controversial that its violence caused several copycat crimes in England and caused Kubrick to remove it from distribution in that country—Kubrick adapted Anthony Burgess’s dystopian 1962 novel of the same name about a charismatic yet sociopathic gang leader named Alex (Malcolm McDowell), who is imprisoned for the rape/murder of a woman but then elects to receive an experimental treatment that will make him nauseous at the sight of sex or violence. Alex is “cured” by the treatment but then becomes a punching bag once released back into the world because he is unable to defend himself. Originally given an “X” rating due to its intense violence and sexual scenes, A Clockwork Orange still managed to receive a Best Picture nomination at the Academy Awards.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

This period drama was based on William Makepeace Thackeray’s 1844 novel The Luck of Barry Lyndon. It stars Ryan O’Neal in the title role as an Irish rogue who climbs his way up the social latter through deception and intrigue. The film was sumptuously gorgeous and notable for Kubrick’s use of cameras that were able to capture the natural candlelight of the era for a glowing, realistic effect. Filmed in Ireland during the “Troubles” between the IRA and Loyalist forces, Kubrick eventually received death threats that forced him to pack his bags and finish the film in England.

Barry Lyndon won four Oscars—more than any other of his films—but was considered a financial failure and a critical disappointment at the time of its release. But time has led to a reappraisal. Roger Ebert wrote in 2009, “Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, received indifferently in 1975, has grown in stature in the years since and is now widely regarded as one of the master’s best. It is certainly in every frame a Kubrick film: technically awesome, emotionally distant, remorseless in its doubt of human goodness.”

The Shining (1980)

As far back as 1966, Kubrick had reportedly told a friend he wanted to “make the world’s scariest movie, involving a series of episodes that would play upon the nightmare fears of the audience.”

This psychological thriller stars Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance, an alcoholic aspiring writer who takes a job as the off-season caretaker of the Overlook Motel, which stays snowed-in all winter in the Colorado Rockies. Since the hotel is haunted, Jack slowly loses his mind and takes his angst out on his loving wife Wendy (Shelley Duvall, who was so tramautized by Kubrick’s insistence on filming some scenes more than 100 times that some believe it led to her lifelong psychological decline) and their son Danny, whose psychic abilities are referred to as a “shining.”

The Shining, based on the 1977 Stephen King novel of the same name, would be Kubrick’s only horror film, but in true Kubrick style, it became widely regarded as one of the best horror movies ever made. Notably, Stephen King, appalled that the film diverged so far from his book, said that The Shining was the only film adaptation of his novels that he could “remember hating.”

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

Coming as it did on the heels of other massively successful dramas about the Vietnam war such as Platoon, Full Metal Jacket—which gets its name from the type of bullets used in Army rifles at the time—would be the only post-1964 film of Kubrick’s not to receive any Oscar nominations.

Based on Gustav Hasford’s 1979 novel The Short-Timers, the film stars Matthew Modine as “Joker,” a Marine recruit at boot camp on Parris Island, SC. The brutally cruel gunnery sergeant Hartman (Lee Ermey) seeks to completely destroy every soldier’s individuality in order to turn them into remorseless killing machines. But Hartman, as well as the other soldiers, prove to be a bit too cruel to a recruit who’s nicknamed “Pyle” (Vincent D’Onofrio), who eventually snaps and kills Hartman and himself in the film’s most memorable scene. The film’s second half takes place in Vietnam after the soldiers complete boot camp and was widely criticized for its perceived aimlessness.

Eyes Wide Shut (1999)

Based on a 1926 novella by Arthur Schnitzler called Traumnovelle (Dream Story), Eyes Wide Shut sees Kubrick moving the setting from Vienna in the early 1900s to New York City in the 1990s. The major theme is sexuality and infidelity. Bill Harford (Tom Cruise) is a New York doctor who is taken aback when his wife Alice (Nicole Kidman) reveals that she’s sexually fantasized about other men. This revelation leads Harford through a dreamlike nightmare in which he attends an upper-class orgy and wrestles with his own temptations. Kubrick reportedly confided to a friend that he thought Eyes Wide Shut was his greatest cinematic achievement. It was not his greatest critical success, although it grossed more at the box office than any of his other films. It also took 400 days of shooting to complete—a World Record for a feature film’s continuous shoot. Kubrick died a mere six days after screening his final edit for Kidman, Cruise, and Hollywood executives. Warner Brothers digitally altered some of the film’s more explicit sexual scenes in order to secure an “R” rating.

If there’s an afterlife, the fact that others got their dirty hands on Kubrick’s final film and changed it after his death must be a source of eternal torment for the legendary auteur.

Uncompleted Kubrick Movies

- In the late 1950s, Marlon Brando contacted Kubrick and asked him to direct an adaptation of a Western novel called The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones. For half a year, Kubrick worked along with fledgling director Sam Peckinpah on a script, but due to creative differences, Kubrick abandoned the project. The film was eventually released as One-Eyed Jacks (1961).

- After filming 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick set his sights on lensing an autobiographical film about Napoleon starring Jack Nicholson in the lead role. He lost financing after a 1970 Napoleon-themed movie called Waterloo failed at the box office.

- A project to which Kubrick lent the working title of Pinocchio was completed by Steven Spielberg in the form of 2001’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

- An ethnically Jewish atheist, Kubrick had planned for years to make a film about the Holocaust called The Aryan Papers, but he abandoned the project in the wake of Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List.

Stanley Kubrick Facts

- Kubrick was asked to direct both The Exorcist and Exorcist II: The Heretic. He turned down both offers.

- As a teen, Kubrick was a huge jazz fan and briefly attempted to become a jazz drummer.

- A lifelong fan of chess, Kubrick explained that learning chess helped him learn “patience and discipline” in decision-making.

- When asked in 1963 to name his all-time favorite film, Kubrick selected Federico Fellni’s I Vitelloni (1953).

- Despite most of his feature films being nominated for Academy Awards, the only personal Oscar Kubrick received during his lifetime was for Best Visual Effects for 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

- Kubrick was entirely self-taught in all aspects of filmmaking. He had no formal training.

Quotes By Stanley Kubrick

“Man isn’t a noble savage, he’s an ignoble savage. He is irrational, brutal, weak, silly, unable to be objective about anything where his own interests are involved – that about sums it up. I’m interested in the brutal and violent nature of man because it’s a true picture of him. And any attempt to create social institutions on a false view of the nature of man is probably doomed to failure.” —Stanley Kubrick

“Anyone who has ever been privileged to direct a film knows that, although it can be like trying to write War and Peace in a bumper car at an amusement park, when you finally get it right, there are not many joys in life that can equal the feeling.” —Stanley Kubrick

“Actors are essentially emotion-producing instruments, and some are always tuned and ready while others will reach a fantastic pitch on one take and never equal it again, no matter how hard they try.” —Stanley Kubrick

“I love editing. I think I like it more than any other phase of filmmaking … Editing is the only unique aspect of filmmaking which does not resemble any other art form—a point so important it cannot be overstressed … It can make or break a film.” —Stanley Kubrick

“I believe Thackeray used Redmond Barry to tell his own story in a deliberately distorted way because it made it more interesting. Instead of the omniscient author, Thackeray used the imperfect observer, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the dishonest observer, thus allowing the reader to judge for himself, with little difficulty, the probable truth in Redmond Barry’s view of his life.” —Stanley Kubrick, on Barry Lyndon

“One of the attractions of a war or crime story is that it provides an almost unique opportunity to contrast an individual or our contemporary society with a solid framework of accepted value, which the audience becomes fully aware of, and which can be used as a counterpoint to a human, individual, emotional situation. Further, war acts as a kind of hothouse for forced, quick breeding of attitudes and feelings. Attitudes crystallize and come out into the open. Conflict is natural, when it would in a less critical situation have to be introduced almost as a contrivance, and would thus appear forced or, even worse, false.” —Stanley Kubrick, on Paths of Glory

“How much would we appreciate La Gioconda today if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: ‘This lady is smiling slightly because she has rotten teeth’ — or ‘because she’s hiding a secret from her lover’? It would shut off the viewer’s appreciation and shackle him to a reality other than his own. I don’t want that to happen to 2001. —Stanley Kubrick, on 2001: A Space Odyssey

“It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation.” —Stanley Kubrick, on 2001: A Space Odyssey

“Alex makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption or wickedness. He is the very personification of evil. On the other hand, he has winning qualities: his total candor, his wit, his intelligence, and his energy; these are attractive qualities and ones, I might add, which he shares with Richard III.” —Stanley Kubrick, on A Clockwork Orange

“[T]here’s something inherently wrong with the human personality. There’s an evil side to it. One of the things that horror stories can do is to show us the archetypes of the unconscious; we can see the dark side without having to confront it directly.” —Stanley Kubrick, on The Shining

Quotes About Stanley Kubrick

“Among those whom I would call ‘younger generation,’ Kubrick appears to me to be a giant.” —Orson Welles

“Stanley is unusually perceptive, and delicately attuned to people. He has an adroit intellect, and is a creative thinker—not a repeater, not a fact-gatherer. He digests what he learns and brings to a new project an original point of view and a reserved passion.” —Marlon Brando

“Stanley was a very stoic, impassive but imaginative type person with strong, imaginative thoughts. He commanded respect in a quiet, shy way. Whatever he wanted, you complied, he just captivated you. Anybody who worked with Stanley did just what Stanley wanted.” —Vincent Cartier, brother and manager of Walter Cartier, profiled in the short film Day of the Fight

“Stanley’s a fascinating character. He thinks movies should move, with a minimum of dialogue, and he’s all for sex and sadism.” —Irene Kane, star of A Killer’s Kiss

“Kubrick had his own approach to filmmaking. He wanted to see the actor’s faces. He didn’t want cameras always in a wide shot twenty-five feet away, he wanted close-ups, he wanted to keep the camera moving. That was his style.” —Tony Curtis, star of Spartacus

“[Stanley was] cold and detached. Very mechanical, always confident. I’ve worked with few directors who are that good.” —Sterling Hayden, star of The Killing and Dr. Strangelove

“If Kubrick hadn’t been a film director he’d have been a General Chief of Staff of the US Forces. No matter what it is—even if it’s a question of buying a shampoo it goes through him. He just likes total control.” —Malcolm McDowell, star of A Clockwork Orange

“They work with Stanley and go through hells that nothing in their careers could have prepared them for, they think they must have been mad to get involved, they think that they’d die before they would ever work with him again, that fixated maniac; and when it’s all behind them and the profound fatigue of so much intensity has worn off, they’d do anything in the world to work for him again. For the rest of their professional lives they long to work with someone who cared the way Stanley did, someone they could learn from. They look for someone to respect the way they’d come to respect him, but they can never find anybody … I’ve heard this story so many times.” —Michael Herr, screenwriter for Full Metal Jacket

“God, he works you hard. He moves you, pushes you, helps you, gets cross with you, but above all he teaches you the value of a good director. Stanley brought out aspects of my personality and acting instincts that had been dormant … My strong suspicion [was] that I was involved in something great.” —Ryan O’Neal, star of Barry Lyndon

“[He was the] nearest thing to genius I’ve ever worked with, with all the problems of a genius.” —John Alcott, cinematographer on four of Kubrick’s films

“There was great tenderness in him and he was passionate about his work. What was striking was his enormous intelligence but he also had a great sense of humor. He was a very shy person and self-protective but he was filled with the thing that drove him twenty-four hours of the day.” —Marisa Berenson, star of Barry Lyndon

“Instead of finding the intellectual spine of a film in the script before starting work, Kubrick felt his way towards the final version of a film by shooting each scene from many angles and demanding scores of takes on each line. Then over months … he arranged and rearranged the tens of thousands of scraps of film to fit a vision that really only began to emerge during editing.” —John Baxter, Kubrick’s biographer

“Stanley would be happy with eight tape recorders and one pair of pants.” —Kubrick’s wife Christiane, on his fondness for machines

“Kubrick’s secretary heard the sound of each book hitting the wall as the director flung it into a reject pile after reading the first few pages. Finally one day the secretary noticed it had been a while since she had heard the thud of another writer’s work biting the dust. She walked in to check on her boss and found Kubrick deeply engrossed in reading The Shining.” —Stephen King

“There was a lot of interest in Eyes Wide Shut before it was released. But the weekend it came out, July 16, 1999, was the death of JFK Jr., his wife and her sister – a black, black weekend. And for Stanley to have died [on March 7, 1999, at age 70] before the film opened… Well, it all felt so dark and strange. Stanley had sent over the cut he considered done to us, Tom and I watched it in New York – and then he died.” —Nicole Kidman, star of Eyes Wide Shut